- Home

- Douglas Draa

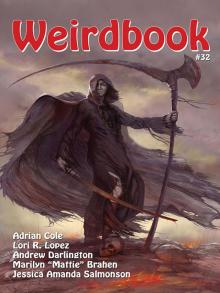

Weirdbook 32

Weirdbook 32 Read online

Contents

Copyright Information

A Note from the Editor

CHILDHOOD’S DREAD, by Taye Carrol

THE OTHER NEIGHBORS, by Daniel Davis

RARE AIR, by Mark Slade

NECROMANCER’S LAIR, by Chad Hensley

THE CHILDREN, by J.E. Álamo

THE HELM, by Chad Hensley

THE RADIANT BOY, by Kevin Wetmore

EX ARCA SEPULCRALI, by Wade German

THE WHISPERER IN THE WOODS, by Peter Schranz

SWEET OBLIVION, by Andrew Darlington

AN UNSOLICITED LUCIDITY, by Lee Clark Zumpe

BLACK CARNIVAL, by Bobby Cranestone

THE LAUGHTER OF GHOULS, by K. A. Opperman

THE HOWARD FAMILY TRADITION, P. R. O’Leary

ODE TO ASHTORETH, by K.A. Opperman

HELL IN A BOXCAR, by Scott A. Cupp

JOROGUMO, by Kelda Crich

CLAY BABY, by Jack Lee Taylor

THE CORPSE AND THE RAT: A STORY OF FRIENDSHIP, by Joshua L Hood

GETTING THIN, by DJ Tyrer

MAYBE NEXT DOOR, by Richard LaPore

CONTAINMENT PROTOCOL, by Leeman Kessler

UNDER A ROCK, by Lori R. Lopez

THE NECRO-CONJURING SORCERESS, by Ashley Dioses

THE CHILDREN MUST BE HUNGRY, by L.F. Falconer

THE ROAD TO HELL, by Kevin L. O’Brien

MAGGOT COFFEE, by Roy C. Booth and Axel Kohagen

WHAT DARK GODS ARE FRIENDS TO ME?, by Chad Hensley

BABY MINE, by Marilyn “Mattie” Brahen

IN BLACKWALK WOOD, Adrian Cole

MY LONGING TO SEE TAMAR, by Jessica Amanda Salmonson

SCARLET SUCCUBUS SHRINE, by Frederick J. Mayer

GUST OF WIND MADE BY SWINGING A BLADE, by Molly N. Moss

PENELOPE, SLEEPLESS, by Darrell Schweitzer

Copyright Information

Weirdbook #32 is copyright © 2016 by Wildside Press LLC. All rights reserved. Published by Wildside Press LLC, 9710 Traville Gateway Dr. #234, Rockville, MD 20850 USA. Visit us online at wildsidepress.com.

Publisher and Executive Editor

John Gregory Betancourt

Editor

Doug Draa

Consulting Editor

W. Paul Ganley

Production Manager

Steve Coupe

A Note from the Editor

Well, it’s time for another issue of Weirdbook! This is #32 or, if you prefer, the second issue of our relaunch.

There wouldn’t have likely been another issue of Weirdbook if #31 hadn’t been such a huge success. The reception that #31 received was amazing, and it appears that we touched the right chord as far as pleasing the readers went. The critics even seemed to like it. Of course, this is entirely due to the wonderful stories supplied by our contributors.

This issue continues the work started in #31 and offers another cavalcade of weird that has been filtered and distilled through more than a double devil’s dozen of voices…each of whom has a uniquely twisted way of viewing (un)reality.

Thanks for stopping by. I’m positive that you won’t be disappointed.

Faithfully yours,

—Doug Draa

CHILDHOOD’S DREAD, by Taye Carrol

The dread comes in on red berries and frozen breath, when the leaves have gone from golden and ochre to brown dyed dead. The red sets a startled contrast to the brown, yet together they are somehow fitting, a sanguine sign of what’s to come. That first morning when the lackluster color scheme can be denied no longer, is always a solemn one. I never know what signals the exact moment of the dreads fulfillment at the same time to everyone, but when the morning comes, the children are wrestled off early to school, still bleary eyed and too asleep to sensor their complaints fully. I’ve always been extra carefully quiet, well behaved on that morning, no matter how early I’m rushed off to school, cold cereal the consistency of peas there’s no time to warm, still sitting like a lump of coal in my stomach even when in-room lunch begins. We try to pay attention, really we do, but it is hard, even for those of us who are older, who didn’t cry and beg and hang on our parents hems when the bus arrived. I’ve always thought the unlucky ones are chosen that way, that it’s always the ones who fail to act right, be good when the time comes, that tips the scale. I’ve never actually proven this but it helps keep my fear at bay throughout the long day until it’s time to return home.

Today the early morning rituals will be my last as a child. Though children aren’t allowed to help their parents with the daily sacrifice, can’t even watch, almost everyone has at some point or another. They get bigger, the sacrifices, starting at the summer solstice as if the shortening days might never reverse themselves otherwise. With so many families now, the river and creeks it gives birth to, begin to look rusty after a while and when they finally freeze over the ice is a strange burnt reddish-brown color. Papa says that he can remember when there were fewer families when the ice was the color ice should be and the children skated on it before the solstice. Even before the strange colors in the ice, it was decided that skating or any boisterous activity, should be forbidden since it could lead to the children being less careful about how they acted. Sometimes now we sneak away to the edge of the woods and collect the leaves into piles to jump into. We’re careful not to get caught, though I’ve always feared that even when we think we’ve gotten away with it, there were other eyes watching, keeping track of who hurt with words and who with fists, who shoved and who pulled, who shouted and who cried at nothing at all.

I’ve never wanted to watch what my parents do in the early mornings on the days we stay in bed, pretend disinterest to disguise my fear. I have become good at not counting the animals in our pen, and don’t keep track of the births anymore, even when I’m made to help. Fear has made me careful, helped hone my denial. And so I don’t try to follow my parents when they go to the gathering place to talk about grownup stuff and never, ever try to see what they do when they disappear into the woods with one of the enclosures inhabitants but come back without. The other kids talk about these things in hushed whispers and maybe they even know what they’re talking about. More likely they don’t. I think even talking big can get you in trouble, even if it were clear that you didn’t really break the rules but are just pretending to. I think when it comes down to it that’s as big a sin as if you actually did. The other kids call me goody two shoes since I always behave. Well, not always, but I am usually better than the other kids so to them it seems that way, I guess. It’s a struggle, not wanting to be thought of as good all the time at least by the other kids, yet at the same time not wanting to tempt the attention of the Others, the ones that usually stay outside the circle enclosing the village.

The enclosure is nothing more that sharpened wooden pickets, painted poppy red, the color chosen to keep evil at bay. Though we’re taught to think of the others as justice not evil. But when your parents disappear one day, a trail of russet smears frozen beneath a milky white crust leading from your front door into the woods, justice is not the first thing that most likely comes to mind. At first, papa said, the fence had been painted a deeper shade, more carmine than simple red, until it was decided that crimson was really more dead on. Now it is a bright poppy red, though each year after the first frost when time comes to paint the fence again, there are always those who argue for crimson and a few voices still who argue for the original carmine. Those last are usually the parents of the youngest children, the ones who still have years to go, who know there are still so many things that can go wrong. Not disaster wrong just childishly wr

ong, but enough to decide their fate. I don’t think it matters really. I doubt it would even if we painted the entire fence white. Since the first families had settled here until now, there has never been a year without a reckoning, a harvest and two less mouths to feed.

The first families weren’t really the first. Some had been here before us. We know because they are buried here. The first families were supposed to have picked this spot because of the ones already here, the ones in the ground. They were supposed to have been holy. It should have been a good omen in a time grown strange. Other areas all had their woes. Maybe not a reckoning and a harvest, but something. Maybe something even worse. Every group that left to settle somewhere else when the days had darkened into night and the stars fell from the skies looked for a place of safety, safe from the terrors of their now blackened homeland. Every group looked for signs that their place would not have to wait in terror each year. I don’t think any found such a place. At least that’s what papa says.

This year, like always, my mamma went with some of the women outside the fence to the old burial place. They go in the late afternoon, since the others only are known to come in the early morning. There they measure the distance between the graves of the holy ones buried there before the turn and the coming of the others, before the reckoning, the harvest. They measure with wick string, carefully making sure the length is correct, no extra due to it snagging on a headstone or rock. The length must be exact. Then they cut the string into lengths and use it for candle wicks, making the candles all night long to leave for the Others in the early morning of the winter solstice. They never come before then. It’s as if they wait until the days begin to lengthen bringing with them hope of an early spring and perhaps even a winter without a reckoning. Then once hope begins to bloom, that is when they come. Many families say this is just superstition, the string and candles, that it increases the danger for the whole village. No one is supposed to venture outside the red fence. But each year since my sixth birthday, mama left the safety of the enclosure and each year she returned. I know I will do the same when my turn comes.

The day crawls by but then, suddenly, it is over. All too soon we must go home. Although we get to ride to school today like always, we are expected to walk home. It adds more time for the harvesting, I suppose, without forcing us to stay at school even longer, as if the day is not different enough. We quietly trudge and shuffle along by ourselves, no adult present to hurry our steps. For once even the boys curtail their antics, keep their hands at their sides away from pigtails and ticklish ribs, half-hearted murmurs the slightest of nods to their nature. We crest the big hill, the last rise leading to the valley where the houses sit, and there we stop as if we can decide to never face what is below.

From here the houses look post-card perfect, smoke coming from each chimney, ice crystals sparkling like diamonds on roofs and eaves. The smell of yeasty bread warms us briefly despite the cold, and we breathe deeply at the top of the climb as always, pretending for this instant that there is nothing but the everyday ordinary below. Here we can forget for a minute that for at least one or two of us, nothing will ever be perfect again. Then a long howling sound comes, not so close but just close enough for us to realize once more that it is that day, the day those parents judged wanting are harvested, have already been harvested. Our bodies grow tight and still. Perfectly still. It’s as if we believe if we stand there long enough we can prevent what we know has already happened. The wind stirs, strengthens then pushes like a hand in the small of our backs, forcing us onward, a message that we can only delay the inevitable not prevent it, and it is time to move on.

We trudge down, down, down, towards the waiting houses. Even the boys now make no sound. Tonight, after the big dinner, after we have played with our new toys, those of us who have escaped for one more year will go to sleep in our own beds. Our parents will keep watch through open doors in case this is the year one of us will become too smug and figure what would it hurt to just catch a glimpse. If they could see our faces when the wind whips at our backs, they wouldn’t worry. We will all remain in our beds as we always have this night, and once again we’ll pretend nothing is different tomorrow, that the unlucky house is not gone, a new one erected in a slightly different place, one or two of us now living with different parents. No one wants to live in an unlucky house and yet there will need to be homes for the newly matched couples soon. This year I will live in one of those houses.

As we approach each house one or two of us peels off, eyes deadened and downcast, breath held to disappear through a door quickly opened and shut. Some don’t go in at first. Those who know they were not as good as they should have been linger outside, regret and fear plain on their faces. This is why the scream doesn’t come until later. When it is my turn, I quickly push open the door, enter and shut it carefully behind me lest it slam. I fear if I so much as hesitate I will never be able to move past the yard.

My eyes are drawn to the table in the entryway. The cups of tea and plate of newly baked mandlebracht, a traditional guests fare, are gone, wafer thin china put up for another year. No one uses wedding china except on this day, believing it bad luck to mix potential bad fate with hoped for good. Mom and dad stand in the kitchens doorway waiting for me and I run to them, remembering to breathe again. Before I think, I am crying, both of them hushing me since I don’t have anything to cry about. Even though once tears could be because of either something good or bad, now they are reserved only for the bad. I look out the window at the other houses, and pretend everything is as perfect as the snow blanketed image upon which I gaze.

Then I hear it. The scream. Tim’s scream. It is high and piercing for a boy, quickly descending into what sounds like someone drowning, then fades, the glass between us muffling the sounds of his anguish. He is not my year and for a minute I am relieved that none of the girls in my class will have to marry without their parents there. Quickly, my relief is replaced by guilt and I turn from the window only to be sickened as always by the gaily wrapped presents I now see sitting in front of my room. Though it’s one more thing not talked about, I know my parents did not buy them, that the toys I unwrap will not be found at either of the two stores in our village. I move leadenly to the packages, push down the rising nausea that comes with the grotesque images of the hands that wrapped them, and quickly uncover the gifts inside. Forcing a smile that feels as if it will cause my face to shatter, I look up at my parents only to see a similar expression on their faces. I am too old for toys, have been for several years now but perhaps childhood for the Others is different. If they have a childhood. This year I get a pretend tea set. Even though every other year the gifts are different, each girl gets pretend china in their sixteenth year. their last reckoning as a child.

The gifts are probably supposed to make the day seem better than it really is. It’s not supposed to be thought of as all bad. The day not the harvest. The family that is harvested well, of course it’s all bad for them even though the kids still get left stuff. Then they have to pretend to play with it until they are collected by their second parents. Every family must choose second and third parents, just in case the second are taken also. I bet no one ever wants to be listed as third parents since they know they will have to care for a child or children who had doomed two sets of parents already. It didn’t happen much but it did happen. Last year Katy and Emily lost their second parents and they were now on their third. That’s probably why they seemed so quiet this whole year even in summer when most kids can forget the coming winter, the first frost and the dread.

Emotions swirl in my head and parts of thoughts, the bad ones about “unfair,” and “evil,” and “torturous,” tamped down firmly before they can play out until simple relief overshadows all. I have made it through my childhood without dooming my parents. I am now an adult and pray I will be rewarded for my success by being allowed to live until I see this day as a parent myself. There’s no ceremony, just your last r

eckoning in your sixteenth year. Well, eighteenth year for the boys. So that means when I am matched tomorrow, it will be with someone two years older than me, someone from outside the safe group of my class, someone I don’t know, have perhaps just seen in passing. We’ll go to the gathering place, and the chancellor will read from a list left for him tonight. He’s older. So’s his wife and it’s always someone either without children or whose children are grown and have no children. This makes sure he won’t take whatever knowledge he has of the others and bargain for his own family. No one knows if this is possible but there are stories of the first chancellor put into place the first year of the reckoning. After he and his family had disappeared, the Others left clear instructions on how it was supposed to be done and since then that is how it has been done. They also left instructions and names for the matching ceremony to be read by the new chancellor. Many families balked at the young ages of those who would be matched then shortly after married to each other. A few families outright refused. They’d all disappeared along with their children. That was the only year more than one pair of parents were taken and the only year they’d taken children also. After that everyone followed directions quite strictly. How the others know so much about us, who we are, our names, exactly how many in each year and who is to be matched with whom, who is supposed to be part of the reckoning, is not known, or if it is, it’s never spoken about. If I thought about it too closely I would have to conclude that we are always being watched and so I don’t think too closely.

It will be some time before I am up for reckoning even if I have a baby next year. They don’t take the parents of babies, after all what could a baby possibly do that you could blame its parents for? This is the beginning of the carefree years, those when my parents are past having to fear for themselves and don’t yet have to start fearing for me and for me the same. The other families who are still slaves to the dread will resent us, hate us even, but for now we don’t care. My parents hold each other tightly and for the first time I see what they must have looked like as newlyweds, each one an only child and so both carefree having come through the dread with both sets of parents intact. My father’s eyes find me at the table where I still sit trying to figure out something else to do with my tea set. He gestures to me and I go to where he and my mother stand. They draw me into the circle of their arms and for once I remember not to cry. We stand in front of the fire watching the list of alternate parents, no longer needed, burn. Once even the ashes are gone I can pretend the list never was. For at least this moment, I finally know what it is to be a child. I close my eyes and sigh, held close within the circle of my parents arms and, just this once, just for a moment, indulge in the joyfulness of a future defined by the possibility of “what if?”

Weirdbook 32

Weirdbook 32